A Practical Guide to AI-Assisted Coding Tools

Get Data Lakehouse Books:

- Apache Iceberg: The Definitive Guide

- Apache Polaris: The Definitive Guide

- Architecting an Apache Iceberg Lakehouse

- The Apache Iceberg Digest: Vol. 1

Lakehouse Community:

- Join the Data Lakehouse Community

- Data Lakehouse Blog Roll

- OSS Community Listings

- Dremio Lakehouse Developer Hub

AI-assisted coding is no longer a novelty. It is becoming a core part of how software gets built.

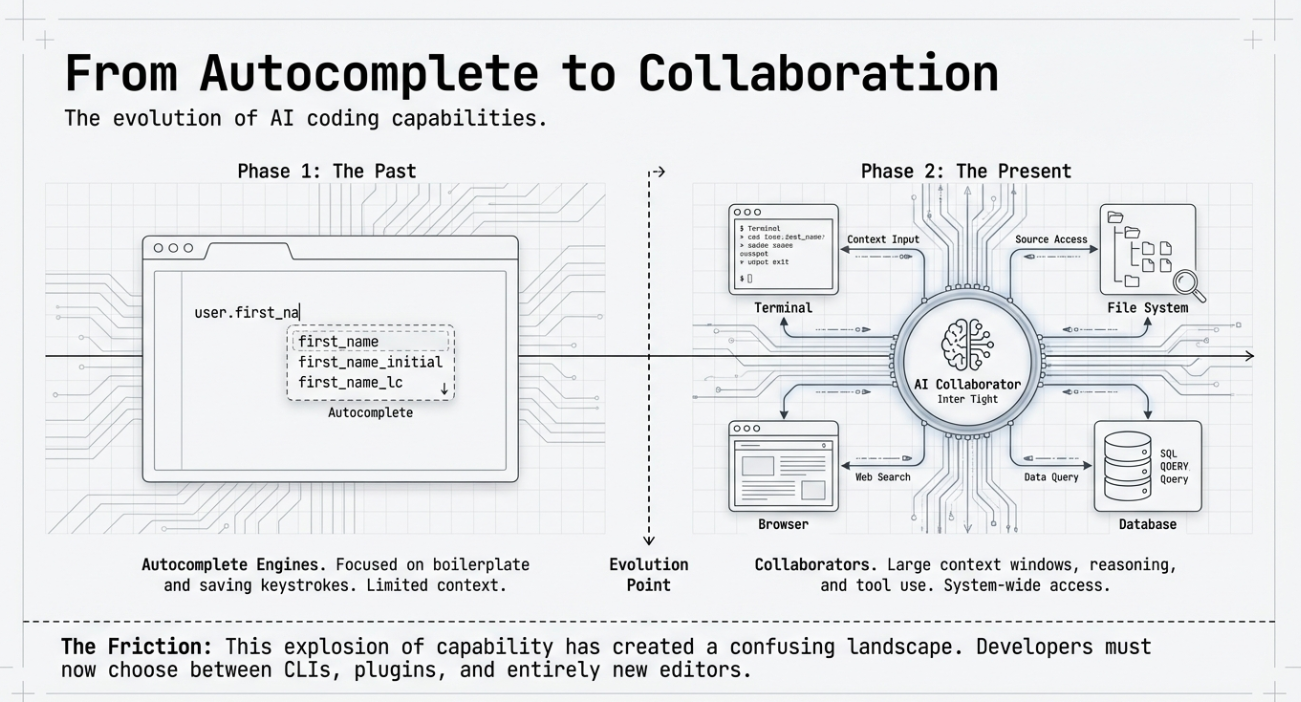

For years, these tools were easy to describe. They were autocomplete engines. They helped you write boilerplate faster and saved a few keystrokes. Useful, but limited.

That changed quickly.

Over the last two years, large language models gained larger context windows, stronger reasoning, and the ability to use tools. At the same time, AI assistants moved closer to the developer workflow. They gained access to repositories, terminals, build systems, tests, and browsers. What emerged was not just better autocomplete, but something closer to a collaborator.

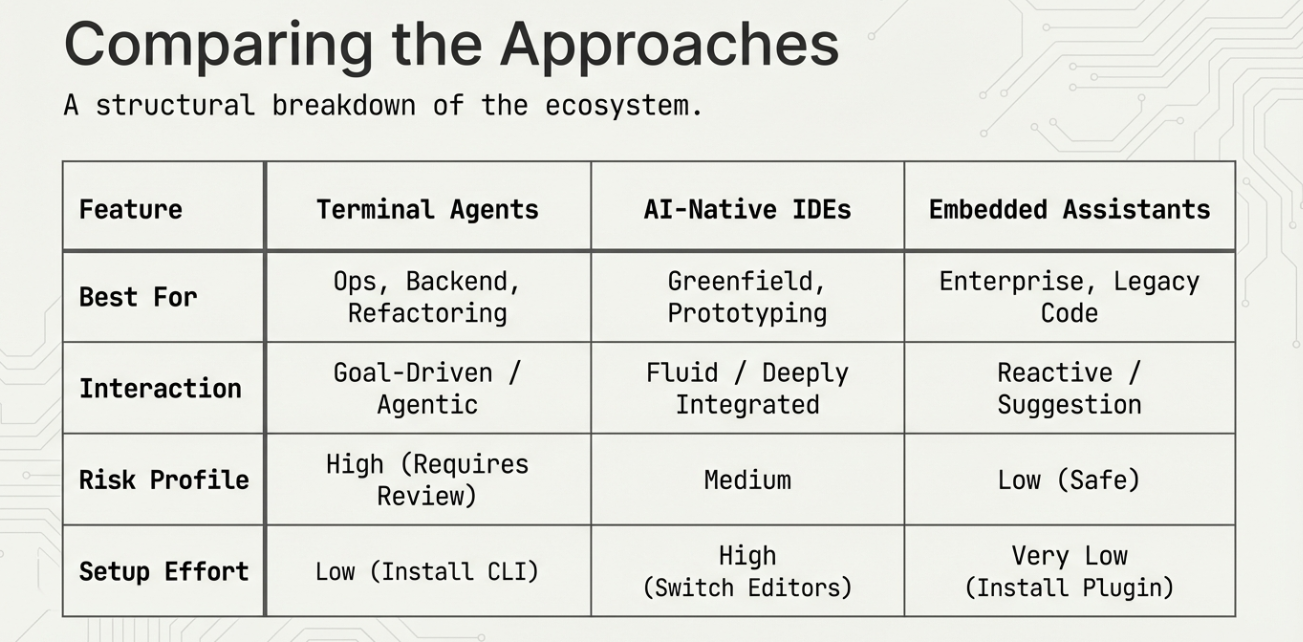

Today, “AI coding tools” covers a wide range of products. Some live in the terminal and act as autonomous agents. Others are AI-native editors built around chat and planning. Many integrate directly into existing IDEs and quietly assist as you type. Each category solves different problems and comes with different tradeoffs.

This creates confusion for developers trying to make sense of the space. Should you use a CLI agent or an IDE plugin? When does an AI-first editor make sense? How much autonomy is helpful before it becomes risky? And how do pricing, privacy, and workflow fit into the decision?

This blog is a practical guide to that landscape. We will categorize the major types of AI-assisted coding tools, compare how they work, and explain when each approach makes sense. The goal is not to crown a single “best” tool, but to give you a clear mental model for choosing the right one for your work.

The Core Taxonomy of AI Coding Tools

Before comparing individual products, it helps to understand how these tools differ at a structural level. Most confusion in this space comes from treating all AI coding tools as the same thing. They are not.

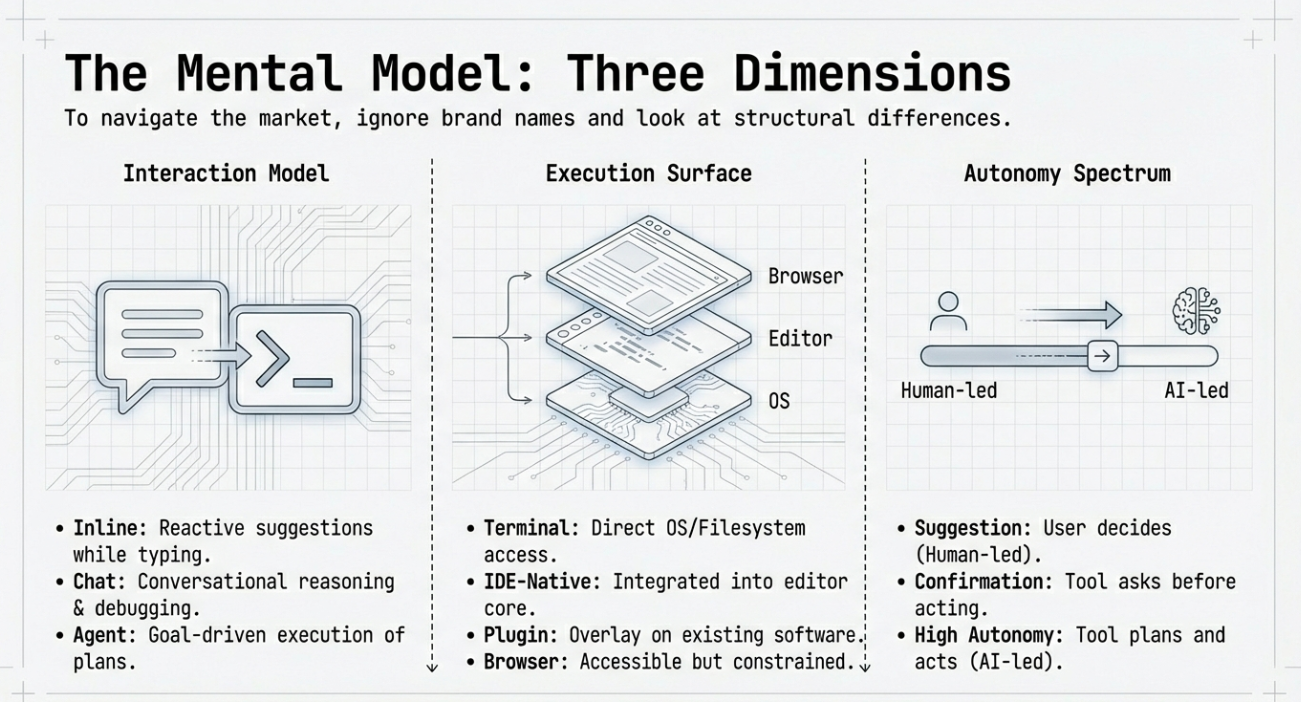

There are three dimensions that matter most: how you interact with the tool, where it runs, and how much autonomy it has.

Interaction Model

Some tools are designed to assist while you type. These focus on inline suggestions and small edits. You stay in control at all times, and the AI reacts to your actions.

Others are chat-driven. You describe what you want in natural language, and the tool responds with explanations, code snippets, or suggested changes. These are useful for learning, debugging, and reasoning about unfamiliar code.

The newest category is agent-based. These tools accept a goal, break it into steps, and execute those steps across files and tools. They plan, act, and revise, often with minimal input once started.

Execution Surface

Where a tool lives shapes how powerful it can be.

Terminal-based tools operate directly on your filesystem and development tools. They can run tests, modify many files, and integrate naturally with scripting and automation workflows.

IDE-native editors are built around AI as a first-class concept. They blend editing, chat, execution, and preview into a single environment designed for iterative work with an assistant.

IDE plugins integrate into existing editors. They trade raw power for familiarity and low friction. You get help without changing how you work.

Browser-based tools prioritize accessibility and collaboration but are usually more constrained in what they can access or modify.

Autonomy Spectrum

Not all AI tools act independently.

Some only suggest. You decide what to accept.

Some perform tasks but wait for confirmation before each step.

Others operate with high autonomy. They plan multi-step changes, run commands, and verify results before handing control back to you.

More autonomy can mean more leverage. It also means more responsibility. Understanding where a tool sits on this spectrum is critical for using it safely and effectively.

With these dimensions in mind, the rest of the landscape becomes much easier to navigate. Each tool is a different point in this design space, optimized for different types of work and different levels of trust.

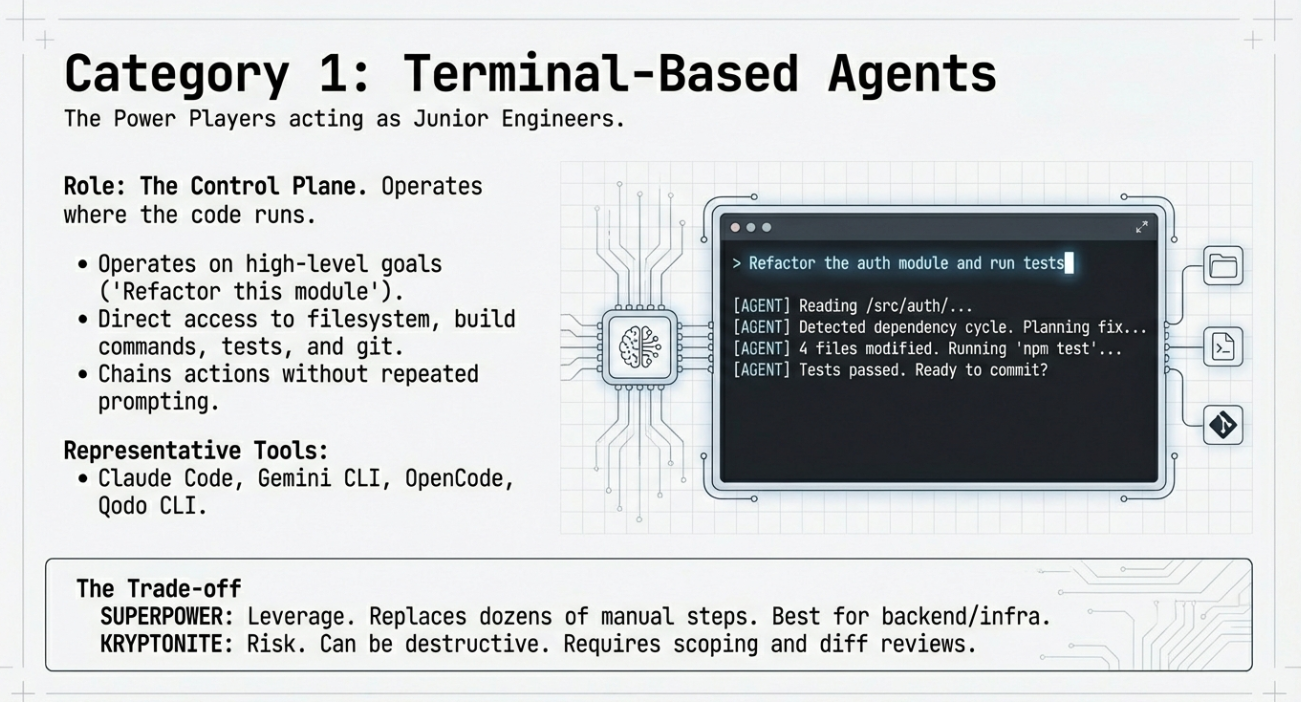

Terminal-Based AI Coding Agents

Terminal-based AI coding agents are the most powerful and, at times, the most intimidating tools in this space. They live where your code actually runs. That gives them capabilities that IDE plugins cannot match.

Instead of suggesting code, these tools operate directly on your project. They can read files, modify directories, run tests, execute build commands, and interact with version control. In practice, this means they behave less like autocomplete and more like junior engineers following instructions.

Why Terminal Agents Exist

The terminal is already the control plane for software development. It is where builds run, tests fail, migrations execute, and deployments start. By placing AI here, these tools gain first-class access to the real workflow rather than a simulated one.

This makes them well-suited for tasks that span many files or steps. Examples include refactoring large codebases, fixing failing test suites, scaffolding new services, or migrating configurations. These are jobs that are slow and error-prone when done manually.

Representative Tools

Tools in this category include Claude Code, Gemini CLI, OpenCode, and Qodo CLI. While they differ in implementation, they share common traits.

They accept high-level goals instead of line-level instructions. They reason about the repository as a whole. They can chain actions together without repeated prompting. Many of them support approval checkpoints so you can review actions before execution.

Some focus on being general-purpose agents. Others emphasize customization, allowing teams to define their own agents for reviews, testing, or compliance checks.

Strengths and Tradeoffs

The strength of terminal agents is leverage. A single prompt can replace dozens of manual steps. They are especially effective for backend, infrastructure, and data engineering work, where tasks are procedural and tool-driven.

The tradeoff is risk. These tools can change many files quickly. They can run commands that alter state. Used carelessly, they can introduce subtle bugs or destructive changes.

Best practice is to treat terminal agents as powerful automation tools. Keep them scoped. Review diffs. Use version control aggressively. Start with low autonomy and increase it only when trust is earned.

Terminal-based agents are not for every developer or every task. But when used well, they represent one of the biggest productivity jumps in modern software development.

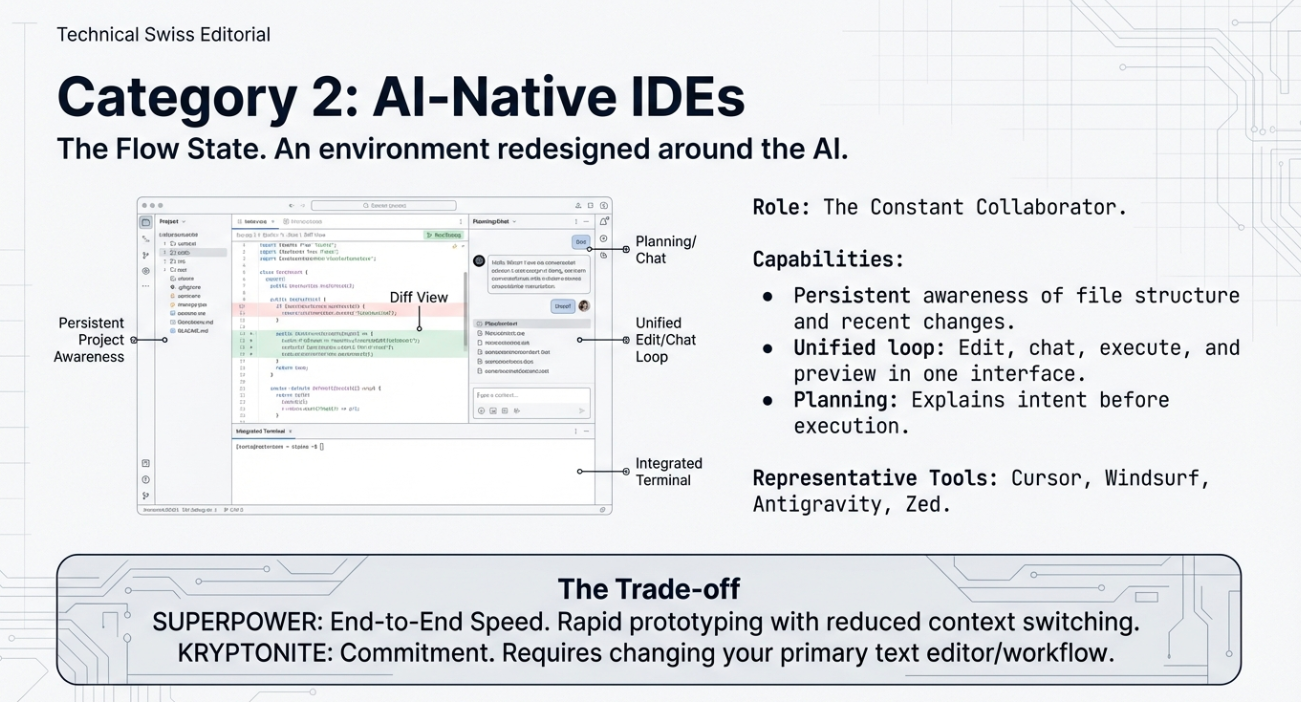

AI-Native IDEs and Editors

AI-native IDEs are built around the assumption that an assistant is always present. Instead of adding AI as a feature, these tools redesign the editor itself to make planning, execution, and iteration flow through the model.

This changes how development feels. You do not switch between typing code and asking for help. The conversation and the code evolve together.

What Makes an IDE AI-Native

In an AI-native IDE, the assistant has persistent awareness of the project. It understands file structure, dependencies, and recent changes without being reminded each time.

These editors usually combine several capabilities in one place. You can ask the assistant to design a feature, generate code across files, run the application, and inspect the results. Some can open a browser, preview a UI, or analyze logs as part of the same workflow.

Another defining trait is planning. The assistant often explains what it is going to do before doing it. This makes complex changes easier to reason about and review.

Representative Tools

Examples in this category include Cursor, Windsurf, Antigravity, and Zed.

Cursor extends the familiar VS Code experience with deep repository understanding and large-scale refactoring capabilities. Windsurf emphasizes agent-driven workflows that keep developers in flow. Antigravity pushes further into full agent autonomy, allowing models to plan, build, and verify changes using integrated tools. Zed focuses on speed, collaboration, and predictive editing, blending performance with AI assistance.

While their design philosophies differ, all of them treat AI as a core part of the editing experience rather than an add-on.

When an AI-Native IDE Makes Sense

These tools shine when you are building features end to end. They work well for rapid prototyping, greenfield projects, and iterative product development.

They are also a good fit for solo developers or small teams, where context switching is expensive and speed matters more than strict process. For some developers, they can replace multiple tools with a single environment.

The downside is commitment. Adopting an AI-native IDE often means changing editors or workflows. For teams with established tooling or strict policies, that may be a barrier.

When the fit is right, though, AI-native IDEs offer a glimpse of what development looks like when the assistant is not a helper, but a constant collaborator.

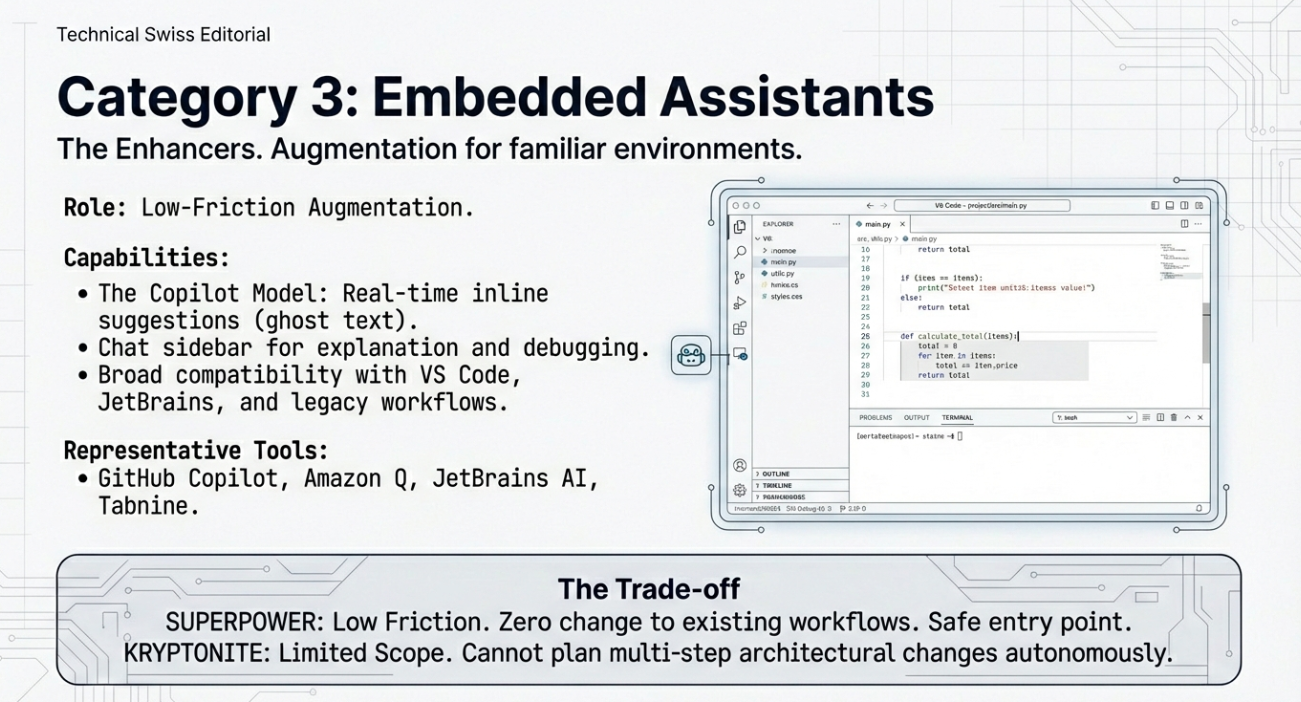

AI Assistants Embedded in Traditional IDEs

Not every developer wants to change editors or rethink their workflow. For many teams, the most practical entry point into AI-assisted coding is through tools that integrate directly into existing IDEs.

These assistants focus on augmentation rather than replacement. They enhance familiar environments with AI capabilities while preserving established habits, shortcuts, and extensions.

The Copilot Model

This category is defined by inline assistance. The AI observes the code you are writing and offers suggestions in real time. You remain in control, accepting or rejecting changes as you go.

Most tools in this group also include a chat interface. This allows you to ask questions about your code, request explanations, generate tests, or debug errors without leaving the editor. The interaction is conversational, but the execution remains manual.

The emphasis is on incremental gains. These tools aim to make each coding session smoother rather than automate entire tasks.

Representative Tools

GitHub Copilot is the most well-known example. Others include Amazon CodeWhisperer and Amazon Q Developer, JetBrains AI Assistant, Tabnine, and Replit Ghostwriter.

These tools support a wide range of IDEs such as VS Code, JetBrains products, and browser-based environments. They tend to work across many programming languages and frameworks, making them broadly applicable.

Some lean toward individual productivity. Others emphasize enterprise features like policy enforcement, auditability, and security scanning.

Strengths and Limitations

The biggest strength of IDE-embedded assistants is low friction. Developers can adopt them with minimal change and see immediate benefits. They are well suited for day-to-day coding, learning new APIs, and reducing repetitive work.

Their limitation is scope. They usually do not plan or execute multi-step changes on their own. They lack direct access to the terminal and external tools, which limits their autonomy.

For many teams, this is a feature, not a flaw. Embedded assistants provide a safe, predictable way to bring AI into the development process without surrendering control.

They are often the right choice when consistency, governance, and gradual adoption matter more than maximum automation.

Pricing Models and Economic Tradeoffs

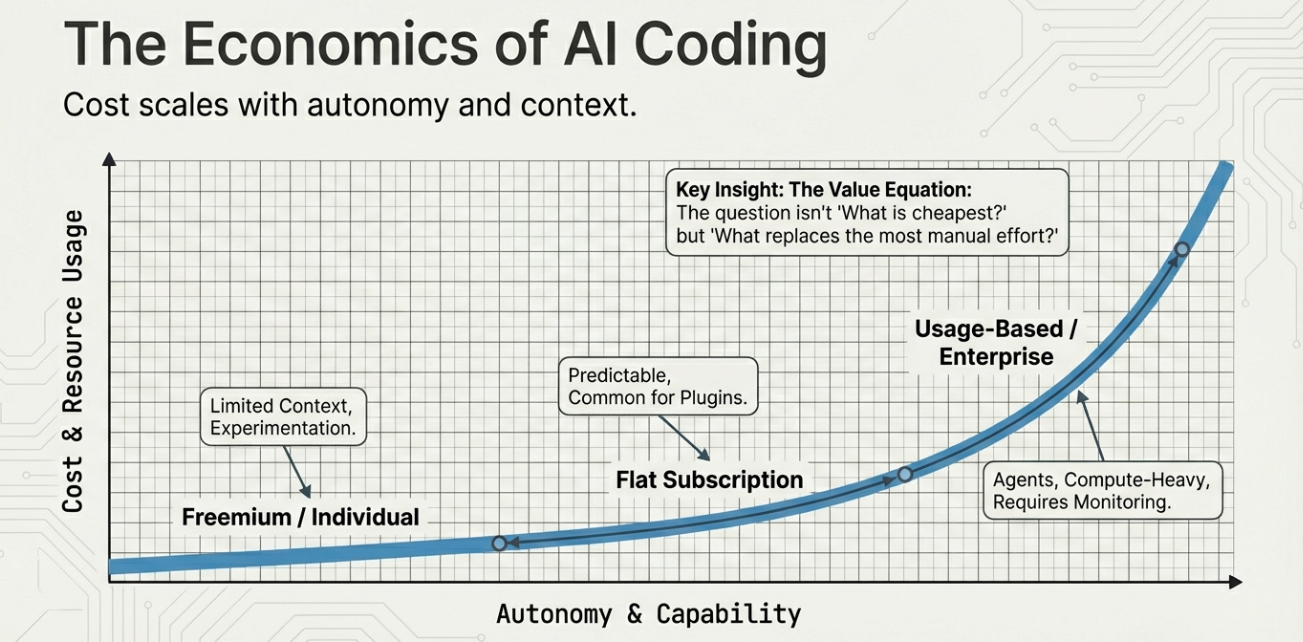

AI-assisted coding tools vary widely in their pricing. Understanding these models is important, because cost often scales with autonomy, context size, and usage intensity.

What looks inexpensive at first can become costly at scale. What looks expensive may replace significant engineering time.

Common Pricing Patterns

One common approach is free or freemium access for individuals. These tiers usually offer limited usage, smaller context windows, or restricted agent capabilities. They are designed to encourage experimentation and personal use.

Another model is flat monthly subscriptions per developer. This is common for IDE plugins and AI-native editors. In exchange for a predictable cost, you get higher usage limits, access to stronger models, and better performance.

Agentic tools often introduce credit-based pricing. Each task or action consumes credits based on model usage, context size, and tool execution. This aligns cost with work performed but requires more monitoring.

Enterprise plans layer on governance features. These include audit logs, centralized billing, access controls, and private deployments. Pricing here reflects not just usage, but risk reduction and compliance.

Cost vs Capability Tradeoffs

More powerful tools cost more because they do more. Large context windows, multi-file reasoning, and autonomous execution all increase compute usage.

Autocomplete-focused tools are usually the cheapest. Agent-based systems are the most expensive, especially when used heavily.

Another factor is model flexibility. Tools that allow you to bring your own API keys shift costs directly to the underlying model provider. This can be cheaper or more expensive depending on how you use them.

The right question is not “which tool is cheapest,” but “which tool replaces the most manual effort for my work.”

Individual vs Team Economics

For individuals, free tiers and modest subscriptions often deliver outsized value. Even small time savings justify the cost.

For teams, the equation changes. A tool that saves minutes per developer per day may justify its cost. One that automates entire workflows may justify much more, but only if guardrails are in place.

Understanding pricing early helps avoid mismatches between expectations, usage, and budget. AI tools are productivity multipliers, but only when their costs align with how they are used.

Workflow Patterns Enabled by AI Coding Tools

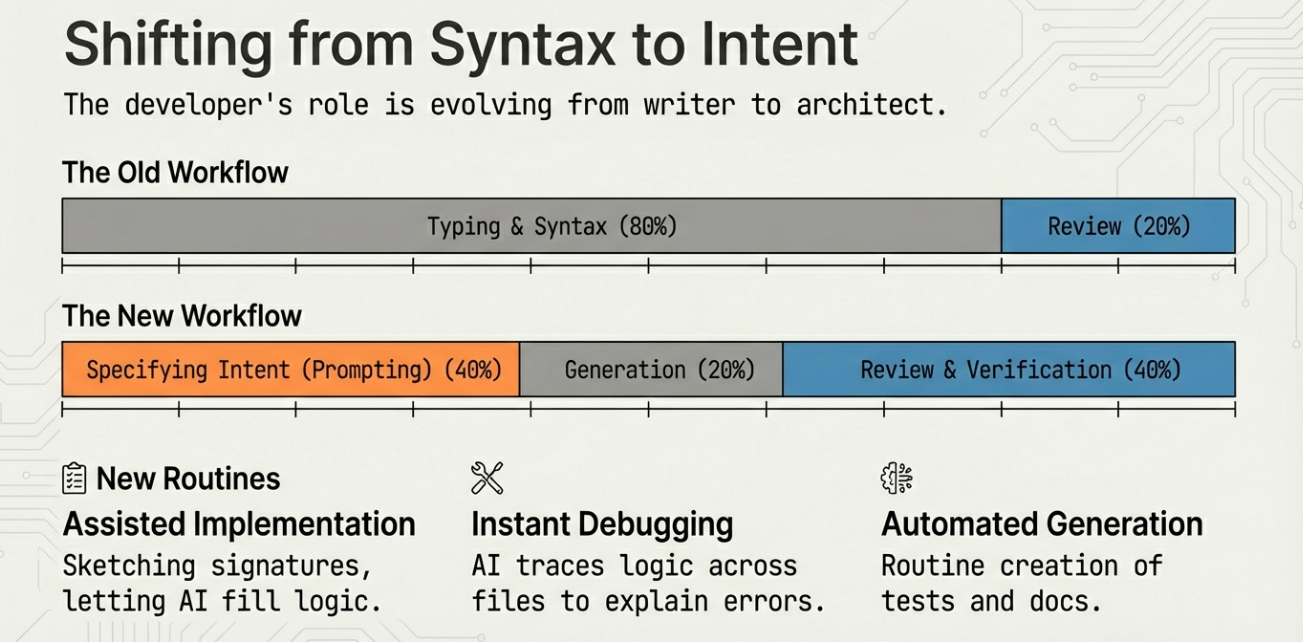

The real impact of AI-assisted coding is not in individual features, but in how workflows change. Once these tools are part of daily work, the structure of development itself begins to shift.

Instead of writing everything by hand, developers increasingly describe intent, review outcomes, and refine results.

Common AI-Driven Workflows

One of the most common patterns is assisted implementation. Developers sketch function signatures or write descriptive comments, then let the AI fill in the logic. This is especially effective for boilerplate, data transformations, and repetitive patterns.

Debugging is another strong use case. AI tools can explain error messages, trace logic across files, and suggest fixes based on context. This reduces time spent searching documentation or past issues.

Test and documentation generation have also become routine. Many teams now generate unit tests, integration tests, and API docs as part of normal development, not as an afterthought.

Agentic Workflows

Agentic tools enable workflows that were previously impractical.

A single prompt can scaffold a new service, refactor an entire module, or migrate configurations across environments. The agent plans the steps, applies changes, and verifies results before returning control.

These workflows work best when tasks are well-scoped and repeatable. Infrastructure changes, dependency upgrades, and large-scale refactors are strong candidates.

The key is oversight. Developers define the goal and constraints, then review the agent’s output carefully. Agentic workflows reward clarity and discipline.

Shifting the Role of the Developer

As AI takes on more mechanical work, the developer’s role shifts toward design, review, and decision-making.

Time moves away from syntax and toward intent. Understanding systems and tradeoffs becomes more valuable than memorizing APIs.

Teams that adapt their workflows intentionally see the biggest gains. Those that treat AI as a novelty often see uneven results.

AI does not remove the need for good engineering practices. It amplifies them.

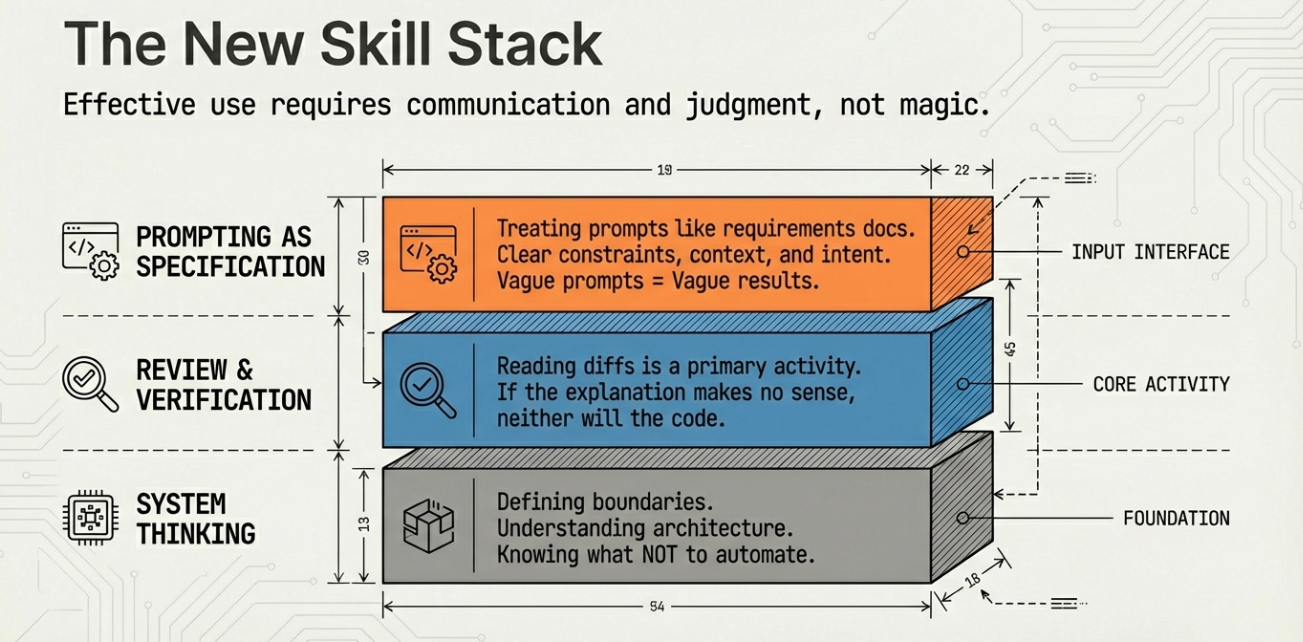

Skills Developers Need in the AI Coding Era

AI-assisted coding changes what it means to be effective as a developer. The most valuable skills are shifting away from speed of typing and toward clarity of thinking.

Using these tools well is not about tricks. It is about communication, judgment, and system-level understanding.

Prompting as Specification

Prompting is best understood as writing specifications in natural language.

Clear prompts describe intent, constraints, and context. Vague prompts produce vague results. The best outcomes come from treating the AI like a teammate who needs good requirements.

Effective developers iterate. They refine prompts based on output, correct assumptions, and narrow scope. This feedback loop is fast, but it still requires attention.

Review and Verification

AI-generated code must be reviewed like any other contribution.

Developers need to read diffs carefully, understand the logic, and verify behavior with tests. Blind trust leads to subtle bugs and security issues.

Knowing how to ask the AI to explain its choices is a useful verification technique. If the explanation does not make sense, the code likely does not either.

System Thinking and Constraints

AI tools are strongest when they understand the system they are working in.

Developers who can explain architecture, performance constraints, and operational requirements get better results. This includes knowing what not to automate.

The more autonomy a tool has, the more important boundaries become. Skilled developers define those boundaries clearly.

In the AI coding era, judgment matters more than ever. The tools move fast. It is the developer’s responsibility to steer them well.

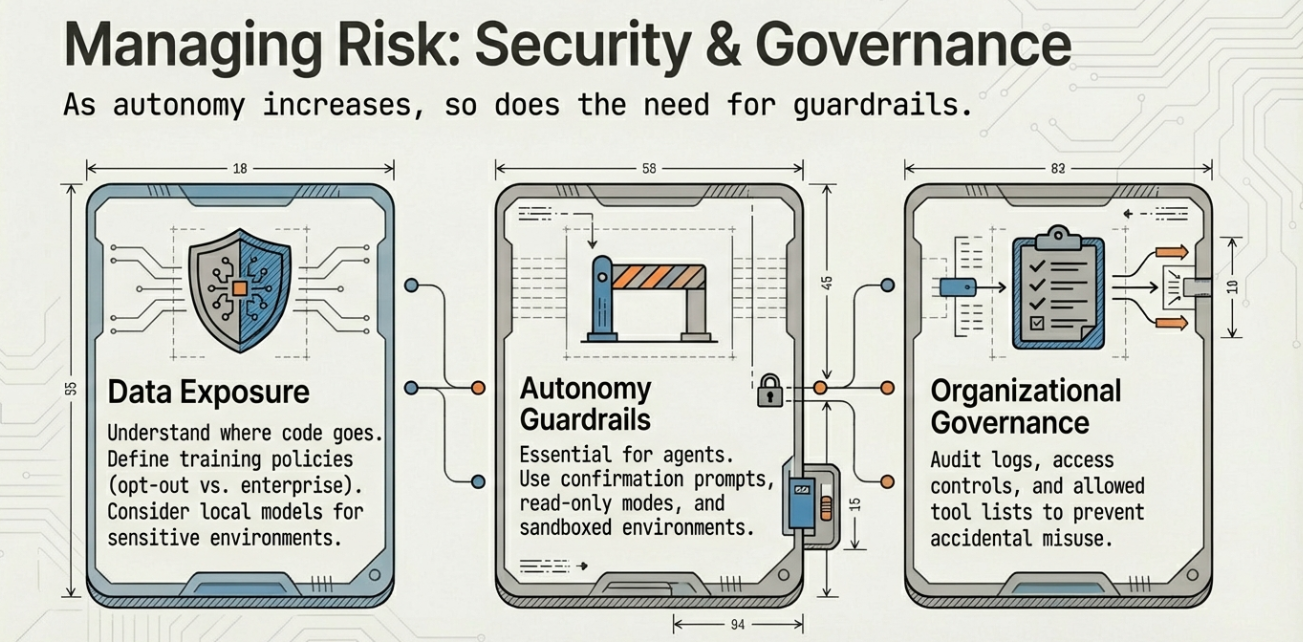

Security, Privacy, and Governance Considerations

As AI coding tools gain access to repositories, terminals, and infrastructure, security and governance move from secondary concerns to first-order design questions.

The risks are not hypothetical. These tools can read proprietary code, modify critical systems, and generate output that looks correct but is not.

Code and Data Exposure

Most AI tools rely on remote models. This means code or prompts may leave your local environment.

Developers and teams must understand what data is sent, how long it is retained, and whether it is used for training. Some tools explicitly guarantee no training on customer code. Others allow opt-outs or require enterprise agreements.

For sensitive environments, tools that support local models or on-prem deployment reduce exposure. This often comes at the cost of convenience or model quality.

Autonomy and Guardrails

Agentic tools increase risk by design. They can execute commands, modify configurations, and affect production systems.

Guardrails are essential. These include confirmation prompts, restricted permissions, read-only modes, and sandboxed environments. Version control is a non-negotiable safety net.

The goal is not to eliminate autonomy, but to scope it carefully.

Organizational Governance

For teams, governance features matter as much as raw capability.

Audit logs, access controls, usage monitoring, and policy enforcement help organizations understand how AI tools are being used. They also help prevent accidental misuse.

Clear guidelines reduce risk. Teams should define which tools are allowed, what data they can access, and what level of autonomy is acceptable.

AI-assisted coding can be safe and effective. It requires intentional design, not blind adoption.

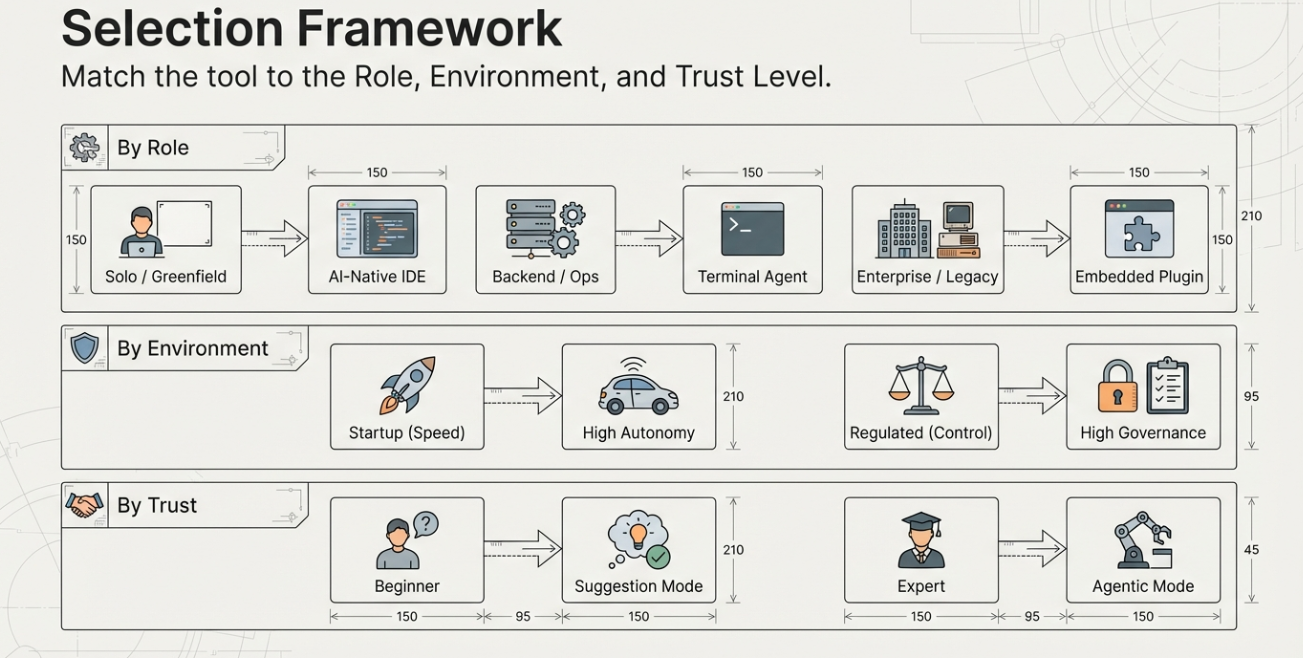

How to Choose the Right Tool for You

With so many options, choosing an AI coding tool can feel overwhelming. The key is to match the tool to your role, environment, and tolerance for change.

There is no universal best choice. There is only what fits your work.

By Role

Solo developers often benefit from AI-native IDEs or terminal agents. These tools reduce context switching and accelerate end-to-end work. They are well suited for prototyping, side projects, and greenfield development.

Backend and platform engineers often gain the most from terminal-based agents. These tools align naturally with scripting, automation, and infrastructure tasks.

Frontend and product-focused developers may prefer AI-native editors or IDE plugins that emphasize iteration, previews, and refactoring.

Teams working in large codebases often start with IDE-embedded assistants. These tools improve productivity without disrupting existing processes.

By Environment

Startups and small teams can afford to experiment. Speed and leverage matter more than strict controls, making agentic tools attractive.

Enterprises prioritize predictability and governance. Tools with clear data policies, audit logs, and controlled autonomy are easier to adopt.

Highly regulated environments may require on-prem models or strict data isolation. This narrows the field but reduces risk.

By Autonomy and Trust

If you are new to AI-assisted coding, start with tools that suggest rather than act. Build intuition and confidence before increasing autonomy.

As trust grows, introduce agents for well-scoped tasks. Avoid full autonomy in critical systems until guardrails are proven.

The best choice is one that fits your current needs and can evolve with your workflow. AI tools are not static. Your adoption strategy should not be either.

The Future of AI-Assisted Coding

AI-assisted coding is still early, but the direction is clear. These tools are moving from helpers to participants in the development process.

The distinction between editor, assistant, and agent is already starting to blur.

Convergence of Tools

IDE plugins are gaining agentic capabilities. Terminal agents are adding richer interfaces. AI-native IDEs are absorbing features from both.

Over time, the market will likely converge around flexible systems that can operate at different levels of autonomy depending on context. One tool may act as an autocomplete engine in one moment and an autonomous agent in the next.

Interoperability and Protocols

As AI tools grow more capable, interoperability becomes essential.

Standards for tool access, context sharing, and action execution are emerging. These allow models to interact with editors, terminals, and external systems in consistent ways.

This reduces lock-in and makes it easier to mix tools, models, and workflows.

AI as a First-Class Team Member

The long-term shift is conceptual.

AI tools are evolving from passive assistants into collaborators that can plan work, execute tasks, and verify results. This does not remove the need for human developers. It changes where their effort is spent.

Design, judgment, and accountability remain human responsibilities. Execution increasingly becomes shared.

The future of software development is not fully automated. It is more leveraged, more intentional, and more collaborative.

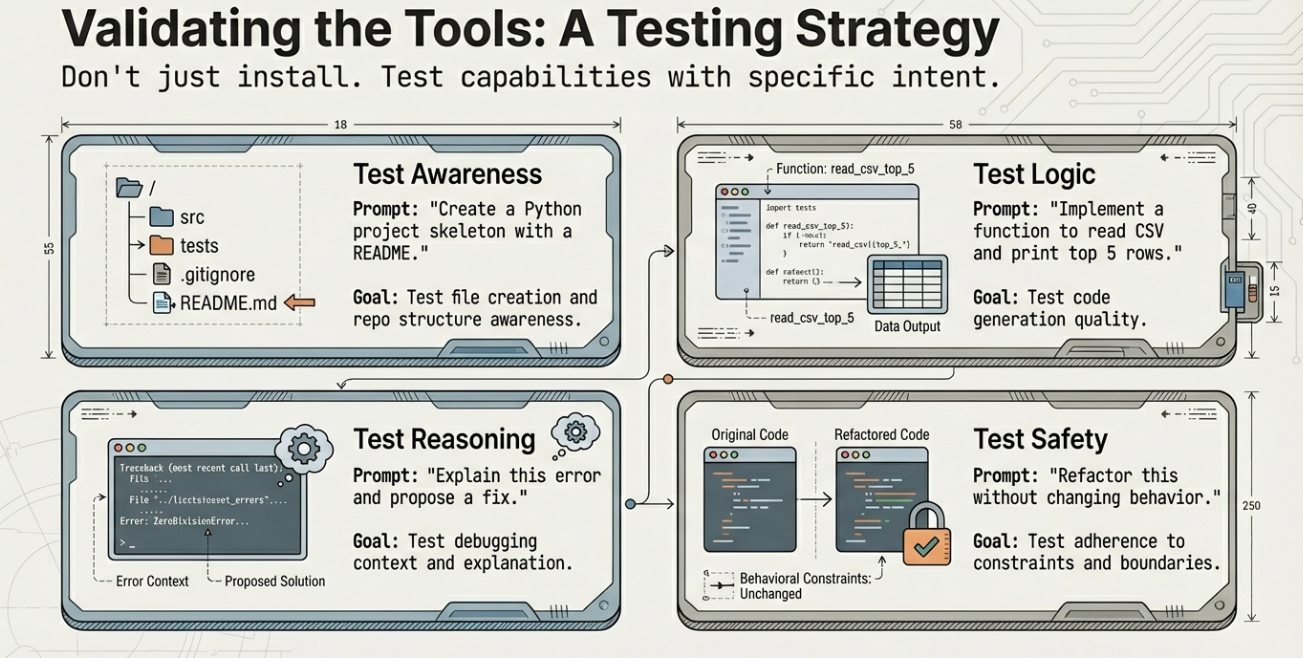

Sample Prompts to Get Started

One of the hardest parts of using AI coding tools for the first time is knowing what to ask. The prompts below are designed to be simple, low-risk, and useful across most tools, whether you are using a terminal agent, an AI-native IDE, or an IDE plugin.

Each prompt focuses on building or modifying something small while helping you learn how the tool behaves.

Prompt 1: Create a Simple Project Skeleton

Use this to test repo awareness and file creation.

Create a simple Python project for a command-line tool.

It should include:

- A README

- A main entry file

- A basic argument parser

Do not add extra features.

This prompt helps you see how the tool structures files and how much initiative it takes.

Prompt 2: Implement a Small Feature From a Description

Use this to test code generation quality.

Add a function that reads a CSV file and prints the top 5 rows.

Assume the file path is passed as a command-line argument.

This works well in IDE plugins and editors. Review the code carefully and run it.

Prompt 3: Explain Existing Code

Use this to test understanding and explanation.

Explain what this function does and identify any edge cases.

Keep the explanation concise.

This is useful for learning unfamiliar code and validating AI understanding.

Prompt 4: Generate Tests

Use this to test correctness and coverage.

Write unit tests for this function.

Use the existing testing framework.

Cover normal cases and one edge case.

This helps establish a review habit and reinforces test-driven thinking.

Prompt 5: Refactor for Clarity

Use this to test refactoring behavior.

Refactor this code to improve readability.

Do not change behavior.

Keep the logic explicit.

Compare the diff to ensure intent is preserved.

Prompt 6: Simple Agentic Task (Terminal or AI-Native IDE)

Use this to test safe autonomy.

Add basic logging to this application.

Use the existing logging library.

Show me the changes before committing.

This prompt checks whether the agent plans steps and respects boundaries.

Prompt 7: Debug a Failure

Use this to test reasoning.

This test is failing.

Explain why, then propose a fix.

Do not apply the fix yet.

Only apply changes after reviewing the explanation.

How to Use These Prompts Safely

Start small. Run tools in a clean project or branch. Review every change.

Pay attention to how the tool interprets ambiguity. If results are surprising, refine the prompt rather than forcing acceptance.

Good prompts are clear, scoped, and explicit about constraints. Treat them like lightweight specifications.

These examples are not about speed. They are about learning how the tool thinks before trusting it with more responsibility.

Conclusion

AI-assisted coding is no longer a single category of tools. It is an ecosystem with distinct approaches, tradeoffs, and philosophies.

Terminal agents offer raw power and automation. AI-native IDEs rethink how development flows. IDE-embedded assistants provide steady gains with minimal disruption. Each has a place, and each serves different kinds of work.

The most important takeaway is intentionality. The value of these tools depends less on which one you choose and more on how you use it. Clear goals, strong review practices, and appropriate guardrails matter more than novelty.

AI does not replace good engineering. It rewards it.

Developers who understand their systems, communicate intent clearly, and exercise judgment will see the greatest benefit. Those who treat AI as a shortcut risk confusion and fragility.

The opportunity is significant. Used well, AI-assisted coding can reduce toil, accelerate learning, and free time for higher-level thinking. The tools are ready. The challenge now is